Traction Devices: What, Why & When

Summary

There are many options available within three broad categories of traction devices - spikes, crampons, and snowshoes – but most day hikers and long distance hikers may find the former to be the most useful, in most circumstances, most of the time.

Hiking in snow and ice conditions, and choosing what traction to wear, is more art than science, and there is simply no replacement for practice and experience.

Crampons and spikes are different tools for different jobs, not comparable alternatives. Crampons will do everything that spikes can do and more, but the reverse is not true.

Traction devices almost always benefit from being combined with hiking poles, an ice axe, or even both (topics beyond the scope of this article).

Traction devices should not be a replacement for reliable, grippy, footwear in snow/ice conditions. Experienced hikers often find that excellent footwear, combined with poles or an axe, may even negate the need for traction devices in low angle terrain typical of many hiking trails.

No traction device is a replacement for patient, well-informed decision-making, a willingness to turn around, and a thorough understanding of alternate route options.

Photo: Jon King/San Jacinto Trail Report, Peak Trail at 9800 ft, San Jacinto Mountains, March 2025.

Even in relatively benign terrain (15-20 degree slope), the optimum traction device will depend on the snow/ice conditions underfoot. With sufficiently deep fresh powder and little or no underlying ice (as shown), this slope is ideal for snowshoes. Postholing with spikes would work too, but would use considerably more energy. After a couple of days of compaction by hiker traffic, and freeze-thaw cycles, the established track becomes ideal for spikes (or even barebooting with grippy footwear for the most experienced hikers). However, any rain before or after the fresh snowfall, turning the slope into ice, and with no preexisting track forming a hiker-friendly route, crampons are needed on this slope.

Getting traction

As trail conditions change in winter, hikers need to be prepared for snowy, icy, and mixed slippery surfaces. Trails that were easy in the summer quickly become treacherous in winter, with or without the right gear. While quality, grippy, hiking boots combined with hiking poles can often provide enough traction for the most experienced winter hikers on well-formed snow trails, many hikers will want some additional traction, at least some of the time.

This is when devices like spikes, crampons, and/or snowshoes go in the pack (or perhaps strapped to the outside). They all attach to footwear in order to provide extra grip while hiking on snow and ice. But not all traction devices were created equal; depending on the type of winter hiking you like to do, you may require more or less grip and mobility. Spikes, crampons, and snowshoes are the three common types of winter hiking aids, and here I discuss what they are, how they differ, and when to use (or not use) each. My emphasis is on day and long-distance hiking, primarily comparing spikes and crampons, with a briefer discussion of snowshoes.

“Better to have it and not need it, than to need it and not have it.”

Spikes (aka Microspikes®, ice cleats)

I use the term spikes for what most people generally refer to as “microspikes”. Technically MICROspikes® is a proprietary name for the product made by Kahtoola.

Over the last 20 years, many different models of spikes have become available. Some of these are devices with small dimples or a reduced number of points, the Kahtoola EXOspikes®, NANOspikes®, and Black Diamond Blitz being the best examples at the upper end of the market.

While these can be very useful in more urban or domestic environments, especially for running, they are rarely the best option for trail hiking in mountainous terrain. While their light weight and small pack size makes them especially tempting, they are rarely the best option for trail use. The devices I recommend to be suitable for angled terrain and mountain use are spikes such as Kahtoola MICROspikes® (including the Ghost model, new in 2025), the Distance and Access models made by Black Diamond, and the various cheaper copy-cat versions available online.

For most hikers, these options are a good solution for winter adventures, as they are versatile, easy to use, and affordable. Composed of chains and small metal points strung between a stretchy rubber frame, these spikes are compatible with almost any kind of footwear you are likely to be using on a trail. For packed snow, patchy ice, and moderately-graded trails, spikes provide plenty of traction. Unless you’re tackling serious summits, glacial terrain, or steep icy conditions, spikes are typically a solid choice for winter traction.

One significant advantage of spikes over crampons is the ability to walk relatively comfortably across areas of bare ground between snow and ice patches. While crampons can be effective when climbing on rock (“dry tooling”), they quickly become very uncomfortable hiking on sections of trail, whether dirt, mud, or rock, in between snow and ice patches.

Spikes have really come to pre-eminence in the past decade or so, in part alongside the explosion in popularity of long-distance hiking. Indeed, they have arguably become too popular, seen as the way to get around the mountains cheaply, easily, and in recent years with minimal weight; all without the expense and training involved in using crampons. Almost invariably, no training is necessary to use spikes. Knowing how to fit them to your own footwear is usually enough to use them.

How you recognize when you are on terrain or in conditions when your spikes are no longer the right tool for the job is discussed below.

Photo: Jon King/San Jacinto Trail Report, South Ridge at 6500 ft, San Jacinto Mountains, March 2025.

Compacted snow represents the ideal underfoot surface for spikes. They are also excellent on icy snow if the slope angle does not justify crampons.

“While crampons can be effective when climbing on rock (“dry tooling”), they quickly become very uncomfortable hiking on sections of trail, whether dirt, mud, or rock, in between snow and ice patches.”

Crampons

For terrain where spikes won’t cut it, opt for crampons. These rigid traction devices strap onto boots and use long, aggressive metal points to bite into ice. Since crampons are burlier than spikes, they’re best for steeper, icier terrain, plus glacier hiking and even vertical ice climbing.

In terms of sport/leisure mountaineering, crampons really began to make an appearance in the 1930s, and at first were actually considered to be “cheating” for mountaineering. Nowadays, crampons (always in tandem with an ice axe) are the minimum essential mountaineering equipment for movement on snow and ice worldwide. Rock, snow and ice are all (relatively) easily climbed in crampons.

With their very diverse range of uses, from relatively benign (but firm) terrain of a glacier, to medium and high-angle terrain of mountaineering, beyond to vertical ice and mixed-climbing, crampons come in many varieties. The weight and bulk scale starts with the ultralightweight aluminium (the Petzl Leopard FL is a very popular hiker model) which is increasingly rigid but still relatively light weight (much like the excellent Kahtoola trail crampon models), and escalate to heavier, but extremely sturdy and reliable, steel models. Serious steel mountaineering crampons can be “semi-automatic”, with a heel bail, or fully “automatic” step-in crampons with both a heel and toe bail.

What kind you get matters. Technical climbing crampons meant for scaling frozen waterfalls differ dramatically from those meant for hiking or even glacier travel (the former generally feature longer points on the toes and must be worn with mountaineering boots instead of regular hiking boots). Crampon bindings are more substantial than the rubber straps used to attach spikes to footwear, making them much more difficult to put on or take off mid-hike. Before purchasing, make sure crampons are compatible with the type of footwear you plan to use (or conversely, if you expect to head into terrain that needs crampons, ensure you have the right footwear). Too often I have seen long-distance hikers attempting to strap lightweight crampons onto trail running shoes, ultimately leaving a precarious mess of dangling straps, crunched up toebox, and a terrifying potential for lateral slippage (both of the crampon and the wearer).

Furthermore, today there are items that definitely class as a crampon but which are designed to fit onto a boot/shoe that is less rigid. You’ll never climb vertical ice in them, but they do offer an additional option which wasn’t available in the past. These fall into the “trail crampons” class, rigid but designed for hiking rather than complex, steep, mountaineering terrain. Again, a good example would be the models sold by Kahtoola.

Crampons really come into their own when the gradient on which you are moving starts to move towards the 20 degree angle or more. That doesn’t seem much, but actually people have an almost universal tendency to greatly overestimate the angle of slopes. Once we are talking about hard-packed snow/ice, with rock thrown in, of an angle about 30 degrees, then crampons should be the default option. They are not just for mountaineers and ice climbing.

Crampons work well for walking on snowy and icy surfaces of easy angles using normal walking technique. They work for climbing on vertical snow/ice/rock faces using only the front-points of the crampon. They also work amazingly well for walking on snow/ice of all gradients using the bottom points to penetrate the snow and using what is generally called “French technique”. Suffice to say that in snow and ice, you can move around on pretty much anything once you know how to move in crampons (properly).

Photo: Jon King/San Jacinto Trail Report, Peak Trail at 10,400 ft, San Jacinto Mountains, February 2023

My crampon tracks barely make an imprint in the snow surface on this 20-25 degree slope, indicating very hard, icy snow. Although the angle is not severe by mountaineering standards, the very open slope and potential for a lengthy fall makes this terrain consequential. This same route was readily passable in spikes (or even barebooting) a few days later once a well-traveled track had created a user-friendly ledge across the slope. Until then, crampons are the only option.

Furthermore, today there are items that definitely class as a crampon but which are designed to fit onto a boot/shoe that is less rigid than has ever been the case in the past. You’ll never climb vertical ice in them, but they do offer an additional option which wasn’t available in the past. These fall into the “trail crampons” class, rigid but designed for hiking rather than complex, steep, mountaineering terrain. Again, a good example would be the models sold by Kahtoola.

Crampons really come into their own when the gradient on which you are moving starts to move towards the 20 degree angle or more. That doesn’t seem much, but actually people have an almost universal tendency to greatly overestimate the angle of slopes. Once we are talking about hard-packed snow/ice, with rock thrown in, of an angle about 30 degrees, then crampons should be the default option. They are not just for mountaineers and ice climbing.

Crampons work well for walking on snowy and icy surfaces of easy angles using normal walking technique. They work for climbing on vertical snow/ice/rock faces using only the front-points of the crampon. They also work amazingly well for walking on snow/ice of all gradients using the bottom points to penetrate the snow and using what is generally called “French technique”. Suffice to say that in snow and ice, you can move around on pretty much anything once you know how to move in crampons (properly).

“Ultimately, no traction device is a replacement for good decision-making, a willingness to turn around, and/or a thorough understanding of alternate route options.”

Snowshoes

Whereas spikes and crampons excel in icy conditions, snowshoes, as the name suggests, are made for deeper snow in which you might otherwise sink. Snowshoes distribute your weight on the snow surface, allowing you to float on top rather than postholing. But for trails with exposed ice or thin, packed layers of snow, snowshoes can become unwieldy without offering the proper traction.

The range of options is not as extensive for snowshoes as it is for both spikes and crampons, but the number of available models with differing features has also expanded greatly in recent decades. Snowshoes with larger decks work well in deep, fluffy powder, whereas smaller snowshoes may be sufficient for moderate snow. Snowshoes designed for steeper and somewhat angled terrain – the MSR Lightning Ascent are the best example of a model that excels in these areas and comes with built-in “crampons” to keep you upright in mixed conditions. Such models have reliable metal frames (simpler models are lighter, but plastic), and include heel lift devices that give relief to the calf and achilles when ascending directly up steeper terrain. Traditionally considered to be slow to take on and off due to the number of straps involved, recent innovations to snowshoes have included webbing combined with a single strap (“Paragon” binding) that allows for very fast and simple on/off.

Although generally unpopular with longer distance hikers due to their weight and bulk, snowshoes are sometimes a necessity when the powder gets deep enough. A fit, experienced hiker will generally be comfortable postholing - perhaps in spikes or even crampons - up to about eight inches (20 cm) of snow depth, but beyond that snowshoes offer a substantial energy saving, assuming the angle of the terrain allows their safe use.

“Although generally unpopular with longer-distance hikers due to their weight and bulk, snowshoes are sometimes a necessity when the powder gets deep enough. ”

Photo: Jon King/San Jacinto Trail Report, San Jacinto Peak, 10,700 ft, San Jacinto Mountains, March 2025.

Spikes or Crampons?

There are the obvious physical differences in appearance between crampons and spikes, especially when considering the wide range of types of both. Spikes generally have fewer points (anywhere from 4-10) whereas crampons have ten, more often 12, and possibly more. Depending on the type of crampon, points are typically one inch (25 mm) or longer, while spikes’ points are typically 10-12 mm (0.4-0.5 inch). This is really the biggest difference from crampons, always less than half the size of crampon points, often much less.

Crampons generally fit best on footwear with a stiffer sole. While some models (“trail crampons”) may be marketed to work with a wider range of footwear, in practice no crampon is optimized to work with a trail running shoe, and a boot would always be the better option. Spikes will fit on any footwear, including training shoes and lightweight, flexible, hiking boots. There are various attachment methods depending on the type of crampon, but generally they secure the heel and the toe of the boot to the crampon. Spikes are usually a rubber attachment fitting on the upper of the shoe (with no specific heel or toe attachment).

Crampons and spikes can seem superficially similar at first acquaintance, which is often the cause of confusion about their relative merits. On terrain that spikes were intended for, they are a better choice than crampons. However, spikes have their limits, and if you are likely to get closer that limit, or exceed it, then crampons are the only sensible choice. Generally, for most hikers with limited or average snow/ice hiking experience, and if the terrain means that a slip is consequential (e.g., sliding further out of control) then spikes are not suitable.

The big risk with using spikes is inadvertently ending up on terrain or in conditions for which they are not suitable – and then having an accident.

Indeed spikes have recently come under increased scrutiny, at least in the mountains of Southern California, where they have been found to have been worn by hikers involved in fatal falls. These incidents have highlighted the dangers of relying on the lightest and easiest traction option, over the skills and experience needed to use the equipment that the terrain required (i.e. crampons).

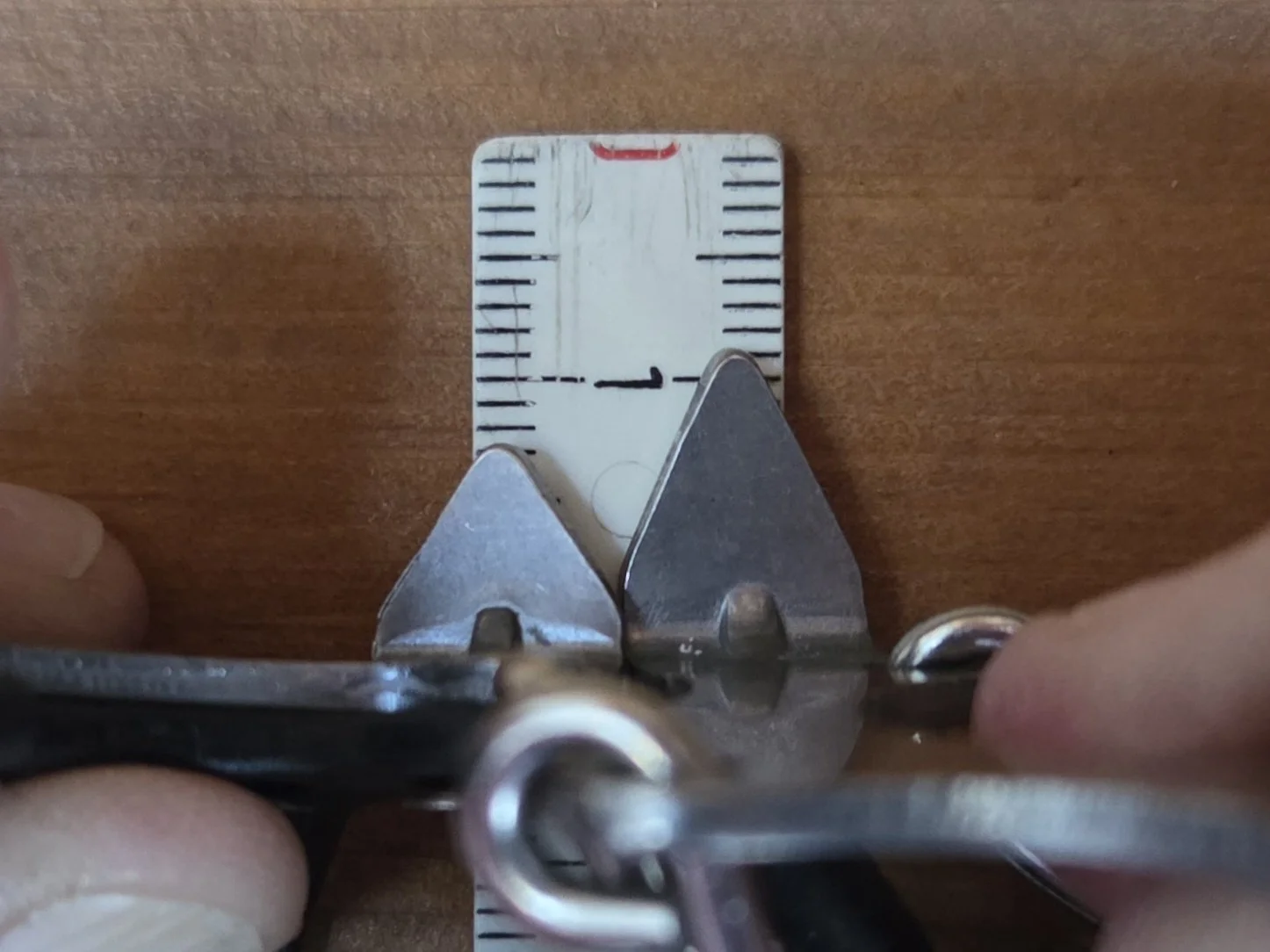

Such incidents perhaps also indicate the difficulties in selecting between types of spikes (which is itself a broad category) as some are much more appropriate for the mountains than others (as described earlier). My own recent extensive testing of the new MICROspikes® Ghost – side-by-side with the original version - has found the former to be useful in powder and firm snow, but the shorter spikes (9mm versus 10.5mm) with a more obtuse spike tip do not provide the same consistent traction in very icy snow and true ice conditions. I have slipped and fallen in Ghost spikes in conditions in which I do not fall in original MICROspikes®. This is worrisome as hikers, especially on multiday routes, will inevitably gravitate towards to the lightest weight option, probably not appreciating that it may not be optimal for the terrain ahead.

This image depicts the difference in spike length between the Kahtoola MICROspikes® Ghost (8mm) vs. the Kahtoola MICROspikes® (11mm)

Several issues factor into the difference between the performance of crampons versus spikes. Crampons will work on anything from 0 degrees (flat) to 90 degrees (vertical). They become more useful on surprisingly low gradients, depending on other factors. Spikes are designed to work on gentle gradients only, relatively flat or maybe up to 10-15 degrees or so. This gradient refers to where you are actually placing your foot, so it may be possible to ascend a mountain slope of 40 degrees if the path switchbacks its way up, meaning that you are always walking on a path of 5 degrees or on a staircase of snow steps on that path. However, the moment the path becomes buried and angles with snow, then you are now on a mountain slope of 40 degrees, (i.e. far outside the sensible limits of spikes).

Crampons give constant “feedback” as to how much grip there is. This allows you to gradually adapt technique, for example transitioning from flat-foot walking to “French technique” on an icy slope to “front-pointing” as it gets steeper (technical topics beyond the scope of this article). Spikes offer a much more binary performance, (i.e. it grips or it doesn’t). Failure to grip is instant and a loss of traction is almost guaranteed. In certain conditions (e.g., a layer of fresh snow sitting on ice) the difference can literally be between one step and the next.

Crampons, used in conjunction with an ice axe, are the only choice when the consequence of losing grip could be an out of control slide. Spikes are really only suitable when the consequence of losing grip is a tumble and something relatively benign like a bruised lower body.

On a gentle gradient, a thin cover of snow or ice on rocks can be one of the most awkward types of terrain to move on in crampons. It’s not impossible but it does require skill and care. On the same gentle gradient, with no significant consequence after slipping, the same thin cover of ice on rocks can be a very straightforward to walk across with spikes. This is when they come into their own.

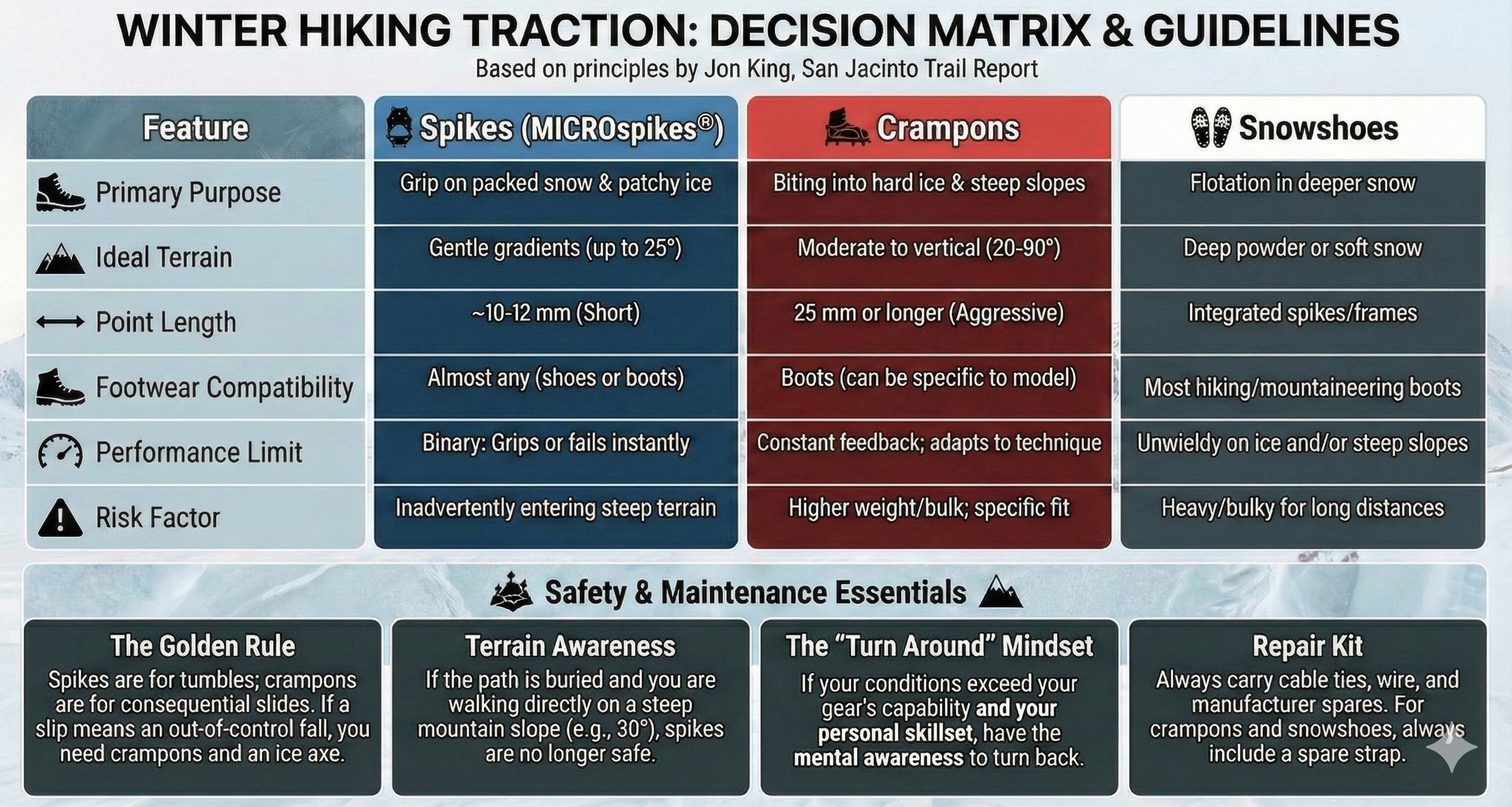

Decision Matrix image created by Gemini 3 Pro (Nano Banana)

Final thoughts

“Better to have it and not need it, than to need it and not have it”. That is my personal mantra for carrying winter hiking gear in snow/ice conditions. I do not compromise when it comes to potentially life-saving equipment. This approach does not necessarily fit neatly with the modern ultralight concept, but I save weight elsewhere by having the best quality-to-weight ratio options available for other equipment.

Having a good sense for the conditions that you are heading into is of course invaluable when deciding what device(s) to carry. There are times, often after a mixed rain/snow storm when conditions underfoot are both variable and unpredictable, when I hike carrying snowshoes, spikes, and crampons (plus of course poles and an ice axe)! While such days are rare, it is not unusual to head into the mountains carrying two of the three broad categories of traction devices. Conversely, even on days when I have little to no expectation of needing them, I always have a pair of MICROspikes® in my pack between the first autumn snow and the late stages of spring snowmelt.

Very experienced hikers find that with high quality footwear and poles, there are some scenarios in which traction devices aren’t critical. Deciding what, if any, traction device will be needed on a given day or hike, comes almost entirely with time and exertion in the mountains.

Notably, a primary concern associated with spikes is inadvertently finding yourself on terrain where crampons are actually the only safe choice. This could come about because you moved onto a steeper gradient than anticipated or because the depth or hardness of the snow or ice is not what you expected, perhaps covering the path completely and making it become part of the overall mountain-side. Spikes generally work great in the scenarios for which they were designed, but they are not appropriate for steep, consequential, icy terrain.

If you have spikes only, and are finding that the terrain and conditions are changing, then the only safe decision is to turn back. However, this requires two things. First, the judgement to recognise that spikes are – both literally and figuratively - out of their depth. Second, the moral courage and self-confidence to turn back, especially if hiking companions are encouraging you to continue with the classic “you’ll be fine”. Ultimately, no traction device is a replacement for good decision-making, a willingness to turn around, and/or a thorough understanding of alternate route options.

Finally, when carrying either crampons, spikes, or snowshoes, it is wise to carry a suitable repair kit to get you off the mountain in the case of a breakage. All traction devices are both essential when they are needed, and somewhat prone to getting broken (given the terrain they are being made to work in). Although generally speaking (and in my own personal experience) the more you pay for a traction device, the less likely or frequently it will fail, do not rely on this in the mountains. For all three traction options, any manufacturer’s spares would be worth carrying, along with a few suitably-sized cable ties (which are the default repair option for so much gear), plus some wire. For crampons and snowshoes, always carry at least a spare strap.